All’s Well That Ends

Well Shakespeare Santa Cruz, 2008

Karen D’Souza – San Jose Mercury News

All’s Well That Ends Well enjoys a curious

status in the Bard’s canon. It is simultaneously one of the most oft-quoted titles ever and yet

one of the least produced of all of Shakespeare’s plays. A bittersweet late comedy that laces

romance with doubt and loss, All’s Well That Ends Well remains very

rarely staged in a Shakespeare market that prefers its comedies light and bright.

Here, the title may well be ironically meant. There are no heroes and no

villains, and though the action concludes with a wedding, there is little to suggest that the marriage

will be a happy one. Shakespeare’s resistance to wrap the heart-melting fable up in neat little

bows has earned it the label of a “problem play,” but that complexity is also what gives this play

resonance in our own deeply ambivalent age. As he put it, “The web of our life is of a mingled yarn,

good and ill together.”

Director Tim Ocel lets the wistful cynicism of the play slowly emerge from

tender performances and a minimalist staging where the only ornamentation comes from the natural

splendor of the glen. Redwood trees rustle in the ocean breeze. Birds chirp overhead. There’s a

naturalism to the sensitive production that heightens the beauties of the text. A cast anchored by

veteran classical actors gives the play a lucid reading that allows us to discover its unexpected

riches.

The genius of the play lies in its sense of ambivalence. Based on a tale

from Boccaccio’s Decameron, this text exudes an almost modern

resignation to the fact that even bright young women like Helena (Rachel Fowler) fall for absolute cads,

like Count Bertram (Erik Hellman), and no amount of bed tricks, mistaken identities and charmed rings

can save the day.

Fowler lights the stage with her Helena, a nimble-witted heroine every bit as

plucky and resourceful as Rosalind or Viola. She loves Bertram so deeply that nothing else matters. It

doesn’t stop her that he is a haughty young lord and she is a humble doctor’s daughter. It

doesn’t stop her that he's selfish and shallow. It doesn't stop her that he would rather die than

hold her hand. The actress nimbly suggests both Helena’s grace and forthrightness and also her

foolish insistence on forging ahead even if charging straight off a cliff. Blinded by love, she can't

see there is no victory in landing an unworthy husband.

Hellman somehow etches enough vulnerability in Bertram to make him seem less

of a pompous scoundrel. He paints a portrait of a callow youth who injures people more out of

recklessness than true cruelty.

While Ocel may not charge the play’s comic scenes with as much

electricity as they crave, he masterfully captures its layers of melancholy. From the dictatorial rage

of the king (Paul Vincent O’Connor) to the sad unwinding of the buffoon Parolles (an astute Allen

Gilmore) and the quiet resignation of the Countess (Beth Dixon) forced to watch as her son sullies their

family name, the play sings with nuance.

John Pribyl, one of three Ashland, Ore., festival stalwarts in the

production, takes obvious relish in the jester Lavatch. Pribyl laces the clown’s riddles with a

disquieting sense of the existential, a feeling that nothing has ever been fair in love and war and that

perhaps nothing ever will be.

In the play’s final scene, when Helena has finally outwitted her man,

he does indeed promise to “love her dearly, ever, ever dearly” but it’s far too early to stamp

this ending happy.

Back to All’s Well That Ends Well Press...Back to Regional Theatre Resume...

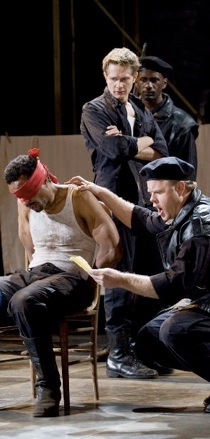

Mike Ryan

All’s Well That Ends Well

Shakespeare

Shakespeare Santa Cruz

2008

Photo: r.r. jones